The degree to which Western relations with Russia have fallen apart since the hopeful days of Mikhail Gorbachev and the early post-Cold War period is mind-numbing. A few key milestones and events are worth revisiting briefly to establish context.

At the end of 1991, Ukraine regained its independence as the Soviet Union dissolved. In previous centuries, parts of Ukraine had been ruled or contested by foreigners including Poles, Lithuanians, Ottomans, and, of course, Russians. But the country’s core identity was just as old as Russia’s, despite President Vladimir Putin’s absurd claim in his infamous and foreboding 2021 essay that Ukraine was not a real country.

In 1994, in an effort to persuade Ukraine to return to Russia the nearly 2,000 nuclear warheads it had inherited from the Soviet Union, Washington, London, and Moscow each promised to guarantee Ukraine’s sovereignty and security, in what was known as the Budapest Memorandum. That turned out to be an empty promise. (It was never intended to be a binding pledge or treaty.)

By the year 2000, when Putin came to power in the Kremlin, many Russian nationalists were smarting over the previous year’s Kosovo war, in which NATO airpower defeated a key Russian ally, Serbia. NATO then forced Russia to accept a secondary (but real) role in the NATO peace enforcement mission in Kosovo, further adding to Russian grievances. (NATO and Russia had cooperated more smoothly in Bosnia starting a few years earlier, however.)

But the worst in relations was yet to come. After initially positive interactions between President George W. Bush and Putin, Russia would be further perturbed by America’s withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002; the invasion of Iraq in 2003; American support for “color revolutions” that challenged former Soviet apparatchiks ruling in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan from 2003 to 2005; the continuing eastward enlargement of NATO, including to the Baltic states in 2004 and a U.S. push in 2008 to put Ukraine and Georgia on an accession path to NATO membership. Then there was the 2011 NATO-led overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya after NATO claimed it would only use force to protect innocents rather than carry out regime change, and American rhetorical support for Putin’s domestic political opponents in the 2012 presidential election.

Unfortunately, Western countries’ efforts to develop positive relations with Russia over the years, such as the creation of the NATO-Russia Council, invitations to Russia to join the Group of Seven and World Trade Organization, summit meetings between Putin and George W. Bush, President Barack Obama’s attempt at a “reset” in U.S.-Russia relations during the Medvedev presidency in Russia, and German/European-led efforts at greater economic cooperation meant less to Putin, who was increasingly turning Russia into an autocracy verging on dictatorship, and who remained bitter and vindictive over the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Putin’s ire grew over this period, as revealed in a signature speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 and his decision to invade Georgia in 2008, a war that nearly resulted in the overthrow of the Georgian government. In 2014, after Ukraine’s pro-Russian president fled the country following protests that started when he abandoned plans for an association agreement with the EU in favor of one with Russia, Putin sent “little green men” to bloodlessly seize Crimea (already home to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet). Then, in a much bloodier fashion, Putin provided aid and direct support for proxy militias in the country’s eastern Donbas region that same year. That conflict never relented. NATO started providing varying degrees of military training and help for Ukraine from 2014-2022, though only on a modest scale, as few foresaw the terrible calamity that was to follow. Meanwhile, Russia completed a 10-year military modernization program; the deck was stacked for what would soon follow.

Overview of the war

The broad story of Russia’s all-out attack on Ukraine, dating from February 24, 2022, can be sketched in roughly the following terms. On that date, after several months of troop buildups combined with preposterous ultimatums to NATO and Ukraine, Russia launched a broad assault against Ukraine with a particular emphasis on the capital of Kyiv. Huge Russian forces descended from Belarus and Russian territory toward the Ukrainian capital—the distance between the Belarusian border and Kyiv, in particular, is about 100 kilometers, making the attack seem like a straight shot. Russia also sought to capture an airport north of Kyiv, perhaps land thousands of troops there, and gain quick access to the city in a lightning strike—not unlike the way it had seized Crimea in 2014.

Fortunately, this time Ukraine was alert to the danger, largely because of American intelligence that had picked up compelling indicators that Russia’s troop buildup along Ukraine’s northern and eastern borders was more than a menacing feint. Ukraine managed to fend off the airfield attack, shooting down Russian aircraft as they approached. Its small infantry teams, using Javelin anti-tank weapons and benefiting from a robust communications grid and good tactical intelligence, also started halting the long Russian armored columns in their tracks along the frozen highway leading from Belarus to Kyiv. Russian troops stayed in their vehicles, failing to provide dismounted cover for the long and vulnerable columns of trucks and combat vehicles, allowing Ukraine to turn a menacing invasion force into a 40-mile-long burning traffic jam. Russian troops also committed massacres of unarmed, fleeing civilians in the nearby city of Bucha.

Thus, Russia’s initial assault on Ukraine, with its obvious intent of toppling the government and perhaps installing a puppet regime that Moscow could subsequently control, was stymied. In a second phase, Russia retreated across a wide swath of territory in northern and eastern Ukraine, giving up close to half the land it had just seized over the ensuing weeks. Then, in the course of the summer and fall, Ukraine made further headway in liberating conquered territories, taking several cities in the east and Kherson in the south by the end of 2022.

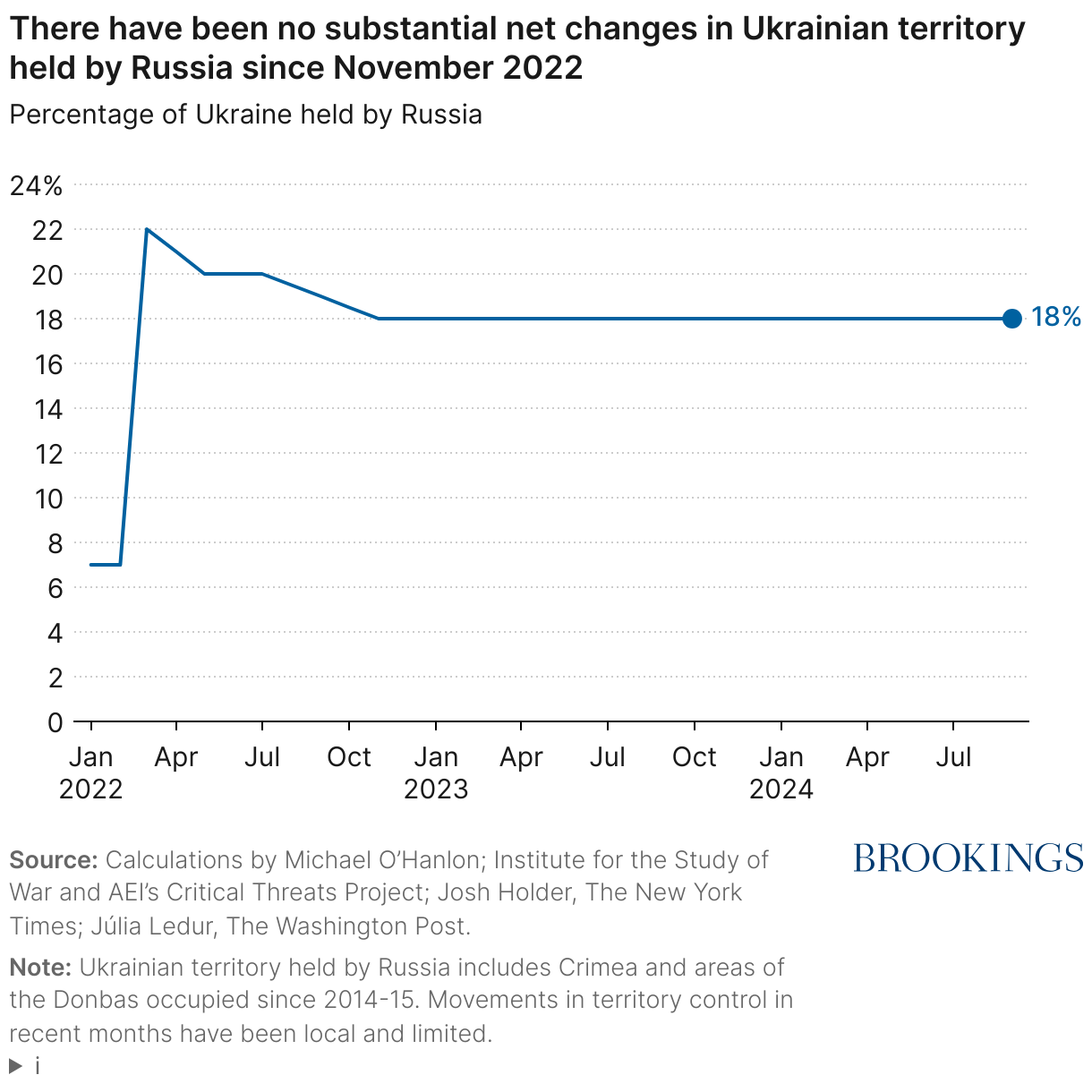

And there the front lines have largely remained ever since. To be sure, there has been movement. Ukraine attempted a broad-sector counteroffensive in 2023, making incremental headway here or there but largely failing, as Russia had dug in and adopted sound defensive tactics, in contrast to its incompetent invasion attempt the year before. Then, in 2024, Russia had its turn at a counteroffensive and had some modest successes in the country’s east, particularly since Ukraine had failed to develop its own fortified defensive positions in many areas (it was still hoping to go back on the offensive) and since Ukraine also had to await a delayed American military assistance package until Congress finally approved it in the spring. Over the rest of 2024, frontline positions stiffened further, and in strategic terms, a general stalemate seemed entrenched, with only modest hopes for either side to break through in 2025.

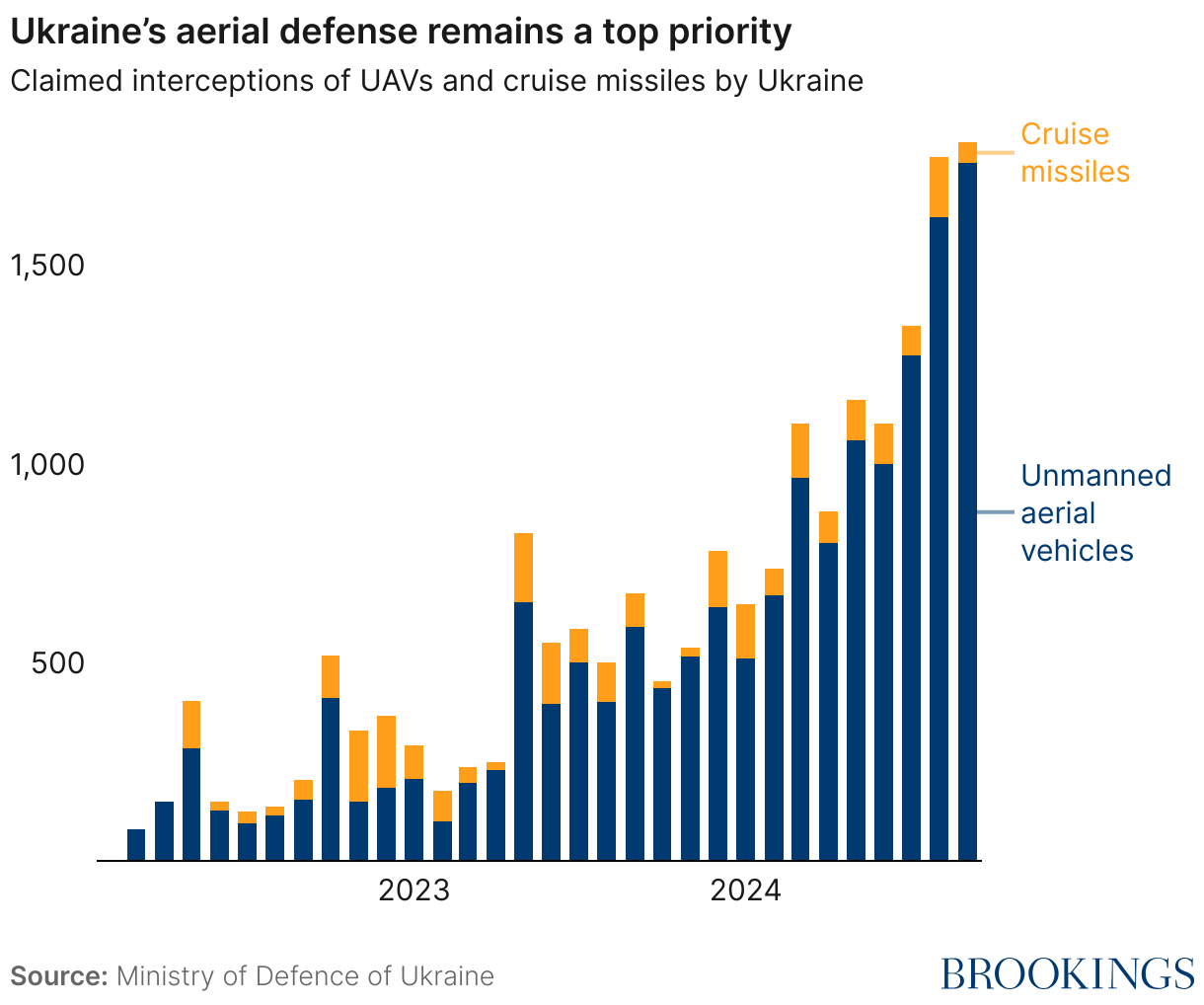

Two more key elements of the story, however, remain to be mentioned. First, Russia’s attacks on Ukrainian cities have been ferocious and quite often barbaric. Cities near the front lines have been hit hardest, but Kyiv and even cities further west have hardly been spared. Ukraine’s air defenses against the barrages of ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as (often Iranian-made) drones, have performed well. Still, the challenge’s sheer magnitude has meant that many Russian weapons have found their targets. Over the winter of 2023-2024, moreover, Russia determined that striking Ukrainian power plants might be its best hope of causing serious hardship, and political leverage, against Ukraine. With roughly half of the country’s power production capability significantly impaired or destroyed, this tactic appears to be potent and likely to be employed again in the coming winter.

More promising and hopeful has been another set of innovations: Ukraine’s use of drones and missiles has caused real shock and setback—and further risk—to Russian positions in Ukraine as well as to the Russian homeland itself. Most notable has been Ukraine’s success in damaging or sinking more than half of Russia’s Black Sea naval fleet, forcing surviving ships to relocate further east, as well as Ukraine’s attack on the Kerch bridge that has probably complicated Russia’s ability to supply its forces in Crimea.

Key battlefield realities and security indicators

The war in Ukraine has been a brutal and bloody fight to date. While it has not reached World War I Western-Front levels of sheer firepower and bloodshed, it often echoes the carnage of that earlier conflict. Even modern technologies such as drones, satellites, and cell phones have not changed this fundamental reality.

Today, by publicly available estimates, Russia fields more troops in Ukraine—almost 500,000—than are in the entire active-duty U.S. Army (452,000 in FY2024). Ukraine’s frontline numbers are lower, by approximately 150,000. But its overall military strength nationwide is in the range of 800,000. Recent changes to Ukraine’s conscription law, lowering the draft age from 27 to 25, suggest that Ukraine can likely sustain such a force at least for the next year or two. Whether it could grow the force further seems more dubious.

The war has essentially reached a standoff along the front lines, at least for the moment. Russia has held about 18% of Ukraine’s pre-2014 territory for nearly two years. Specifically, Russia controls all of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and substantial parts of four additional provinces that it has “annexed”: Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk, and Donetsk (the latter two together constituting the Donbas region). Were Russia to control all of those entities, it would have stolen almost a quarter of pre-2014 Ukraine. That said, Ukraine’s surprise incursion into Russia’s Kursk region on August 6, 2024, demonstrates its capability and resolve to push back and make gains on Russian soil.

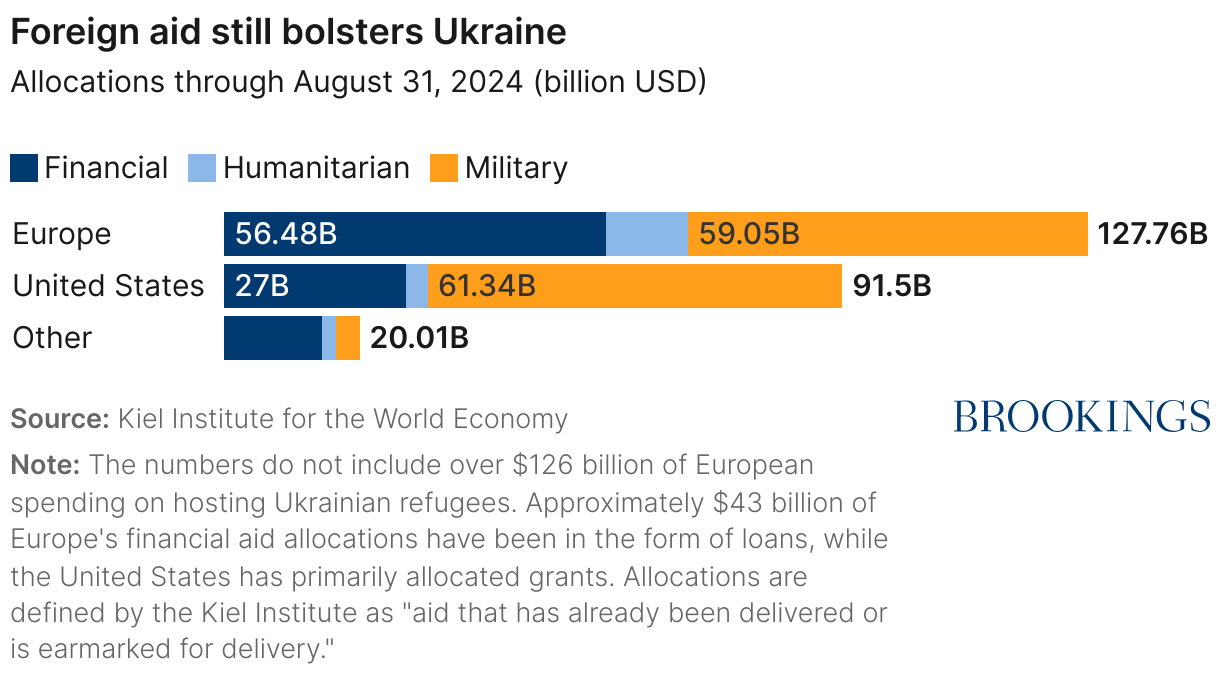

Ukraine is heavily dependent on foreign aid to support its war efforts. The United States has prioritized military assistance and provided approximately $55.7 billion in military aid. European donors have provided almost as much military aid and more economic as well as humanitarian and refugee support; Japan, Canada, and others have helped as well. However, recent U.S. support has been subject to intense debate and Congressional inaction, forcing Ukraine to make difficult choices such as withdrawing from the key town of Avdiivka in February 2024 due to depleted supplies.

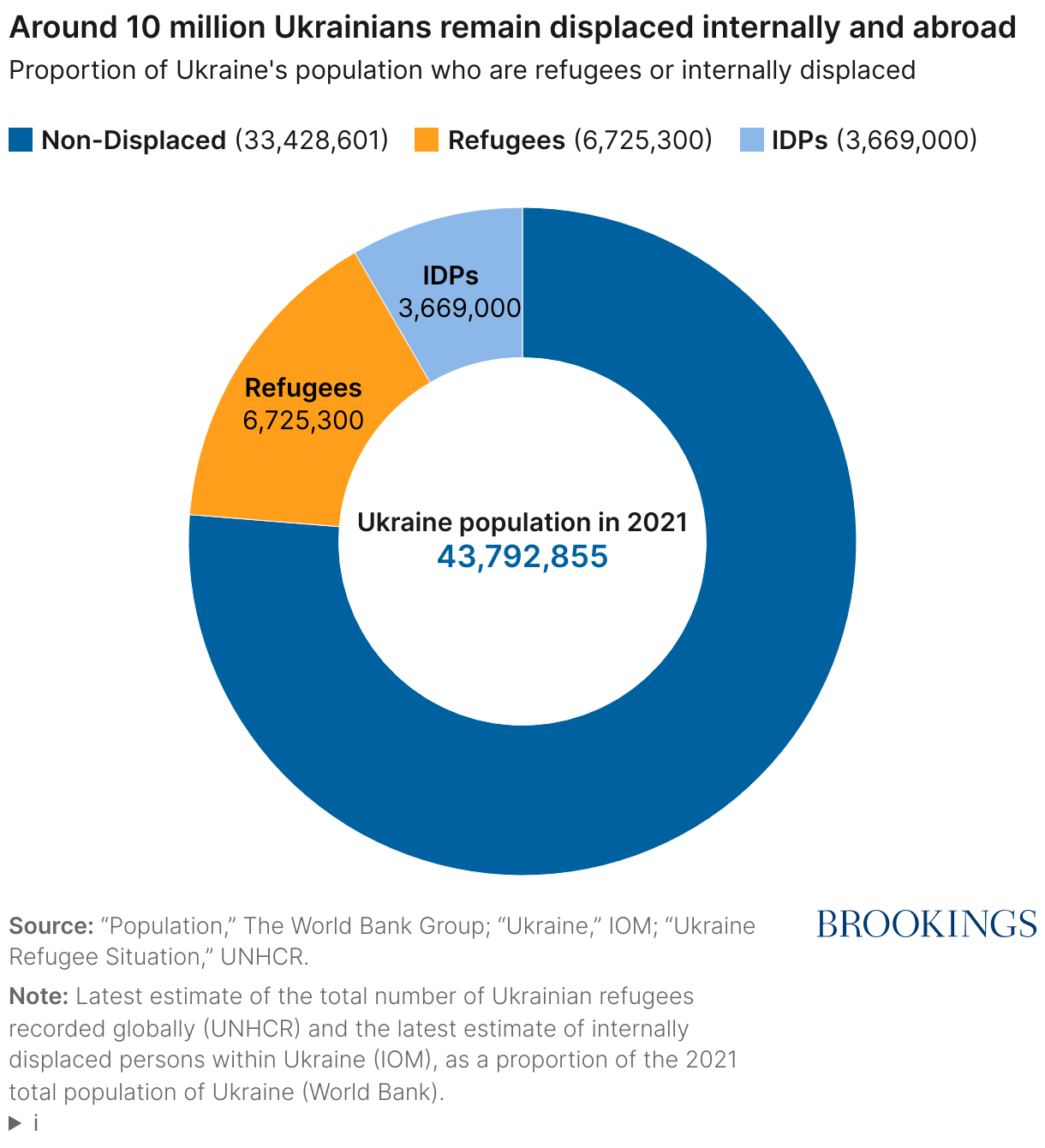

Casualty estimates have been unofficial, uncertain, and piecemeal throughout the conflict. It is neither in Kyiv’s nor Moscow’s interest to divulge accurate and comprehensive figures. However, this is probably now a million-casualty war, counting killed and wounded on both sides. Russia has lost more troops than Ukraine; Ukraine has lost far more civilians, since the war is happening primarily on its territory. Nearly 5 million Ukrainian citizens are now living under Russian rule, with uncertain prospects for their future well-being; Russia’s kidnapping of Ukrainian children has been part of the basis for the International Criminal Court arrest warrants for Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, Russia’s presidential commissioner for children’s rights. Almost a quarter of Ukraine’s 2021 population has fled, with over 6.7 million Ukrainian refugees still living abroad, including 5 million in Europe, and an additional 3.7 million remaining internally displaced. When the fighting ends, the return of many of these Ukrainians will be vital for the country’s economic recovery and democratic vitality.

This has been a war of drones, to be sure, as well as modern accurate missiles (on both sides) and anti-missile systems. In September 2024 alone, Ukraine claims to have intercepted 1,753 UAVs and 53 cruise missiles. However, a growing number of Russian missiles have been breaching Ukraine’s aerial defenses. Russia has been firing larger missile barrages, overwhelming Ukrainian air defenses and hitting strategic targets such as weapons factories, railways, and power plants, as well as essential civilian infrastructure such as hospitals and schools. According to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Ukraine only has about 25% of the air defenses it needs to defend itself. Yet, even if Ukraine’s Western allies respond to pleas to send more air defenses, it is not guaranteed that Ukraine would be able to protect itself against Russia’s new and improved tactics.

The war has also been, perhaps in the first instance, a war of artillery. Early in the war, after its initial attempt at a quick victory failed, Russia resorted to its time-tested method of massive artillery bombardment of Ukrainian frontline positions and cities it aimed to capture. Daily Russian usage rates have often exceeded 10,000 rounds, sometimes reaching two to three times that amount. With increased production from Russian industry (supplemented by munitions from North Korea and factory equipment from China), Russia may be capable of sustaining this pace indefinitely. Despite having most of the world’s top high-tech industrial producers on its side, Ukraine has struggled to maintain a firing rate of 2,000 or so rounds a day and may have dropped well below those levels recently. Even if Washington lifts its imposed restrictions on Ukraine’s use of ATACMS, a long-range ballistic missile, and Western tanks and combat aircraft arrive in Ukraine throughout 2023 and 2024, it is uncertain whether Ukraine will have sufficiently robust maneuver forces to overcome its relative dearth of pure firepower and dramatically shift the war’s momentum come 2025. But then again, war often surprises.

Key economic trends and realities—particularly in Ukraine

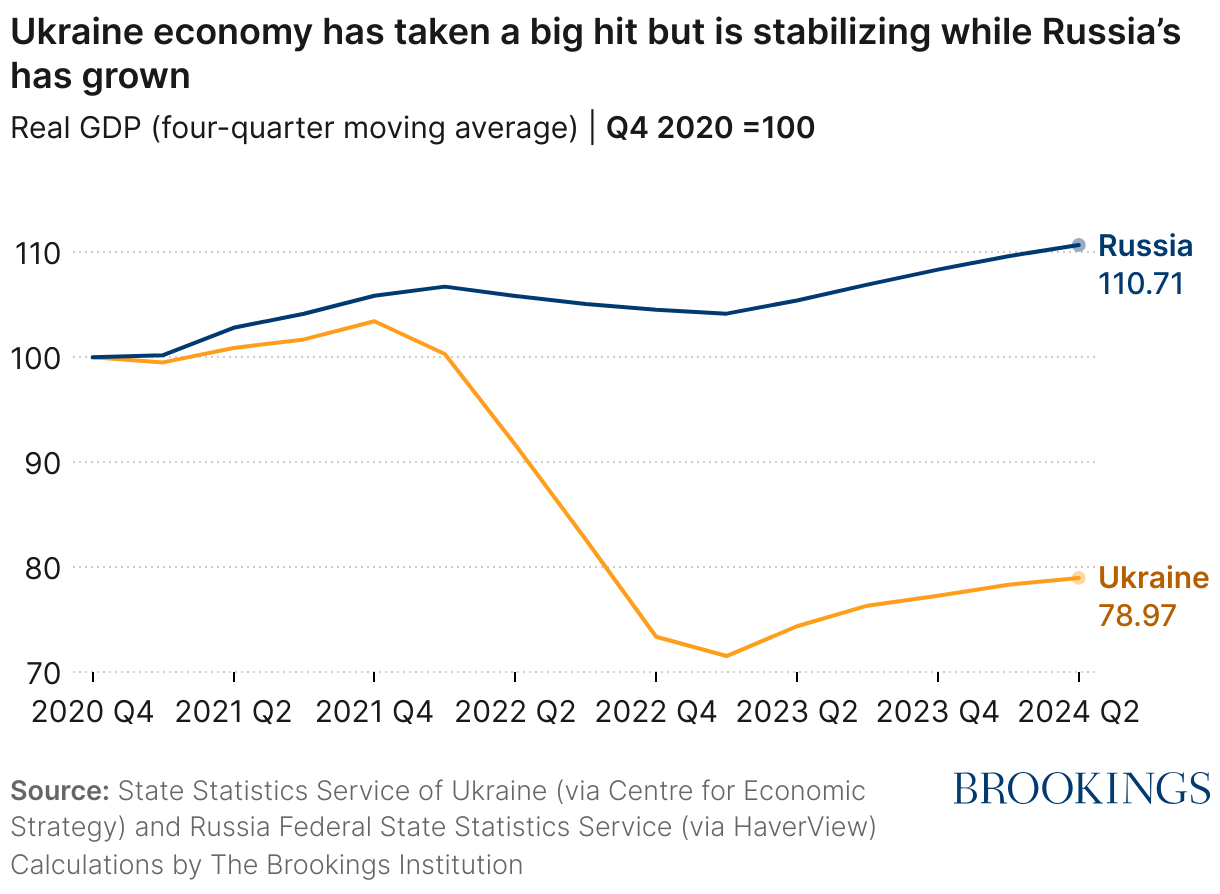

Ukraine’s economy has taken a significant hit from the Russian invasion and continues to be hobbled by Russian attacks on its energy and other infrastructure. It has proven impressively resilient thanks to substantial foreign aid, strong harvests, maintenance of rail and Black Sea export lanes, and a competent central bank. But, as the International Monetary Fund put it in a September 2024 update, “Headwinds are intensifying, and the outlook remains exceptionally uncertain.”

Ukraine’s reliance on foreign aid extends beyond military assistance. Since February 2022, Ukraine has received over $235 billion in assistance from over 40 countries and EU institutions, encompassing military, financial, and humanitarian support. The total reflects aid that has already been delivered to Ukraine or has been earmarked by a foreign government or institution for use by Ukraine. Europe’s steadfast support is evident, with nearly $130 billion in total aid surpassing the United States’ $90 billion (although the great majority of Europe’s financial aid is in the form of loans, whereas the U.S. financial aid is in the form of grants). In addition, European countries have also provided over $125 billion to support and house Ukrainian refugees. Such substantial support underscores Europe’s commitment to winning the war and highlights the dire consequences for the entire continent if Ukraine falls.

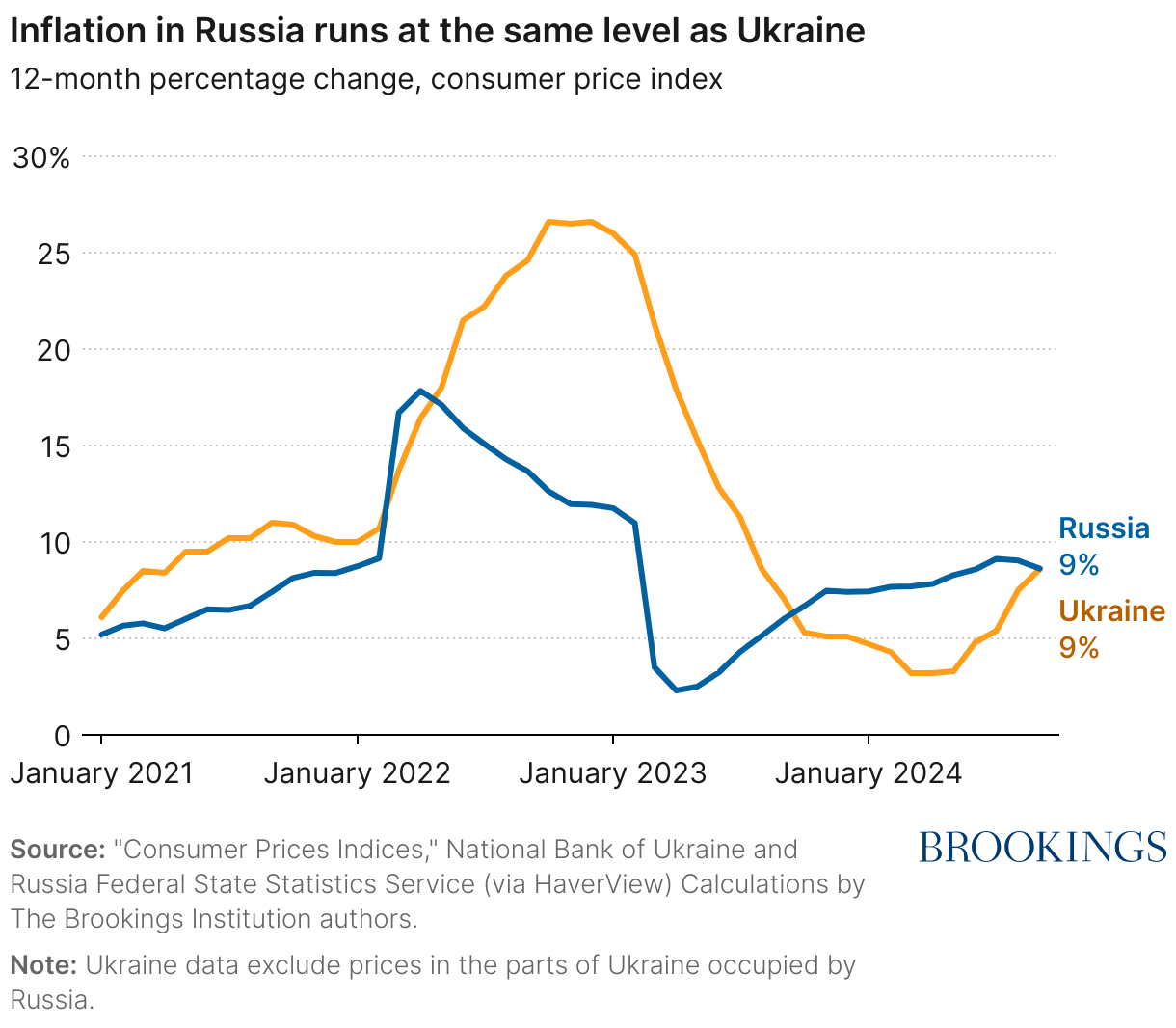

Despite substantive financial assistance to Ukraine, its GDP took a major hit when the war started and stabilized in the first quarter of 2023. Ukraine’s Ministry of Economy projects that growth will drop off in the second half of 2024. Meanwhile, Russia’s economy has grown since the start of the war largely due to its continued defense spending and ramped up operations from supporting industries.

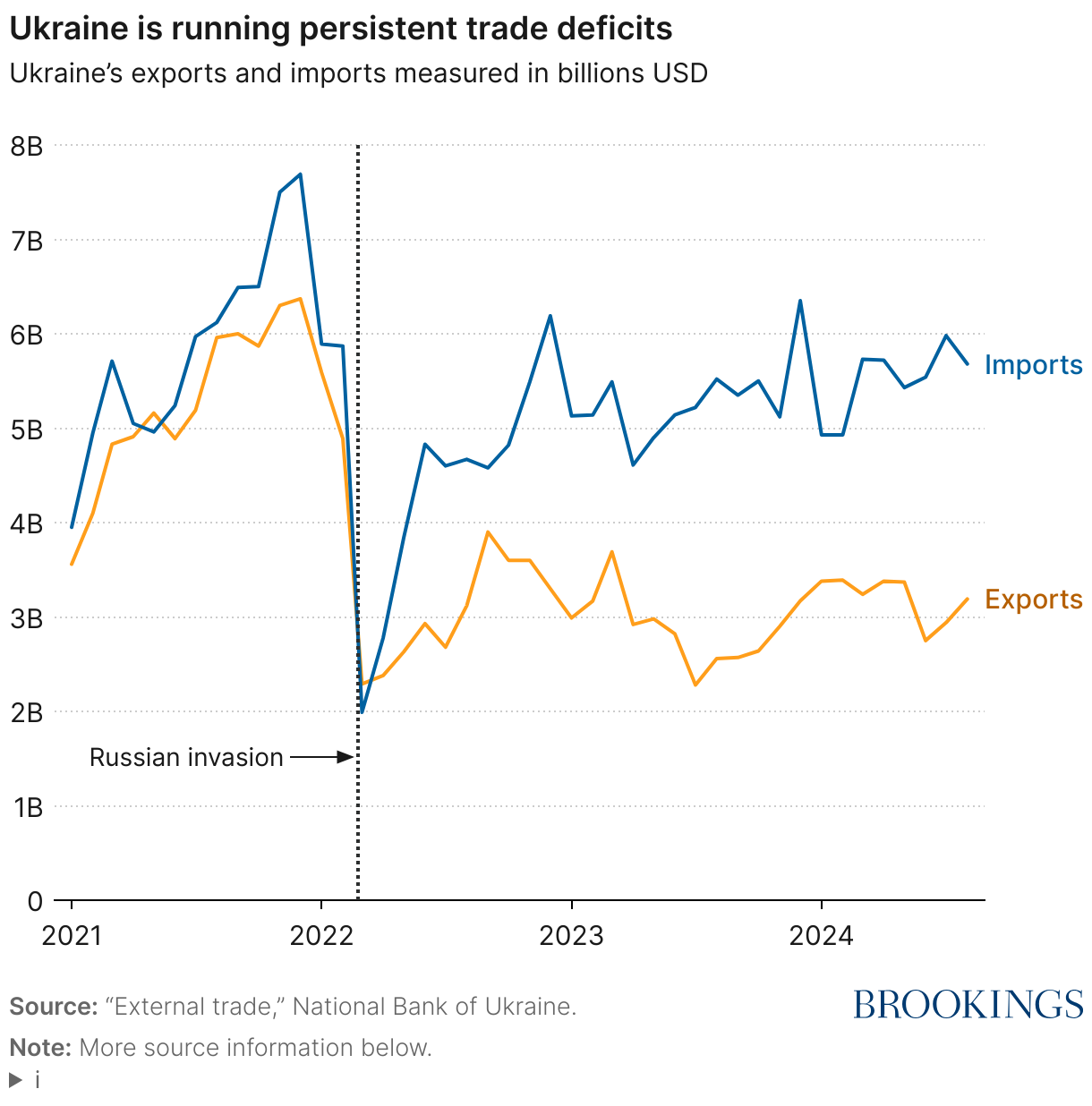

Despite its continued exports of grain, oilseeds, and metals, Ukraine is running persistent trade deficits. While the value of imported goods has risen close to prewar levels, on average, goods exports remain more than 39% below 2021 values.1

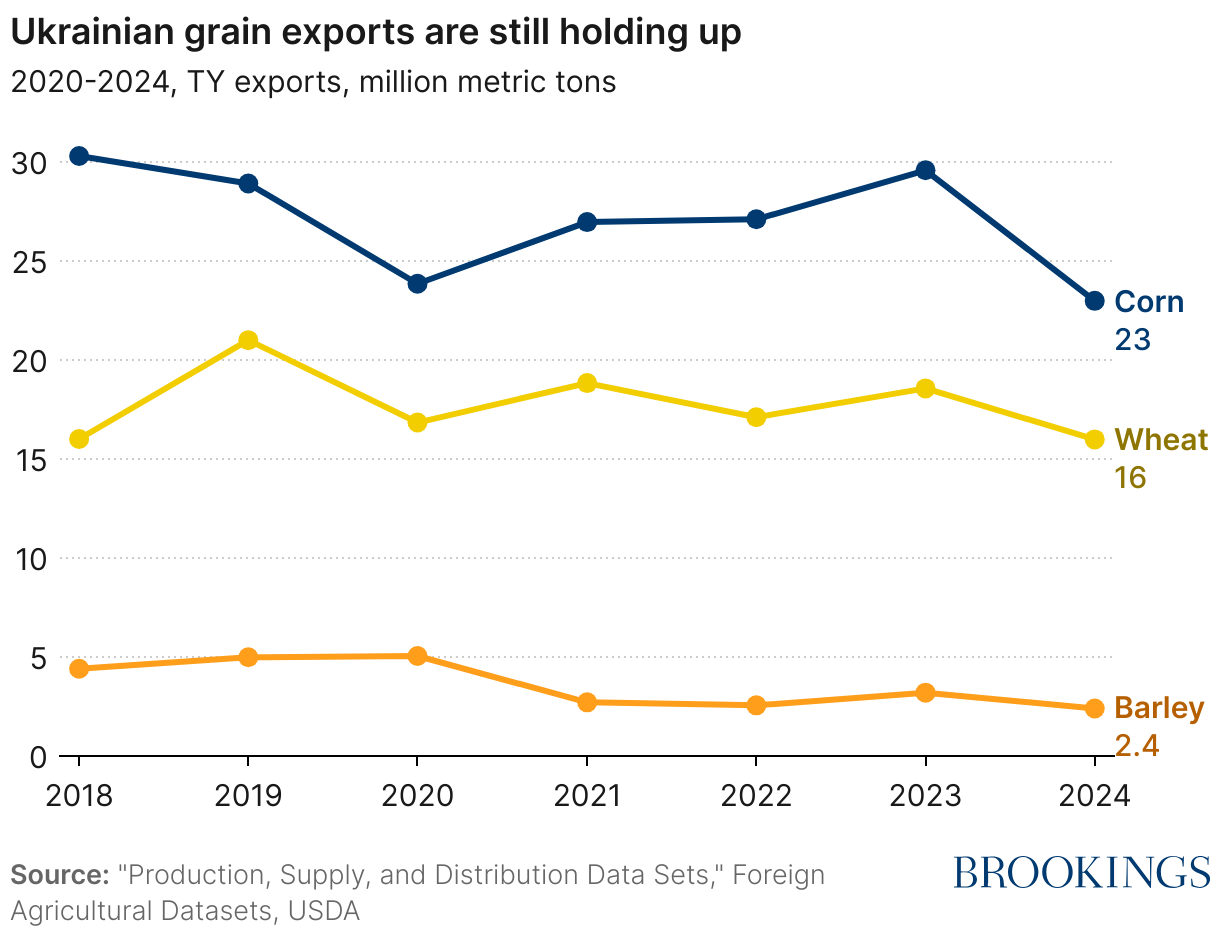

The establishment of a new corridor in the Black Sea has prevented a breakdown in Ukrainian grain exports, despite a fall in the last year.

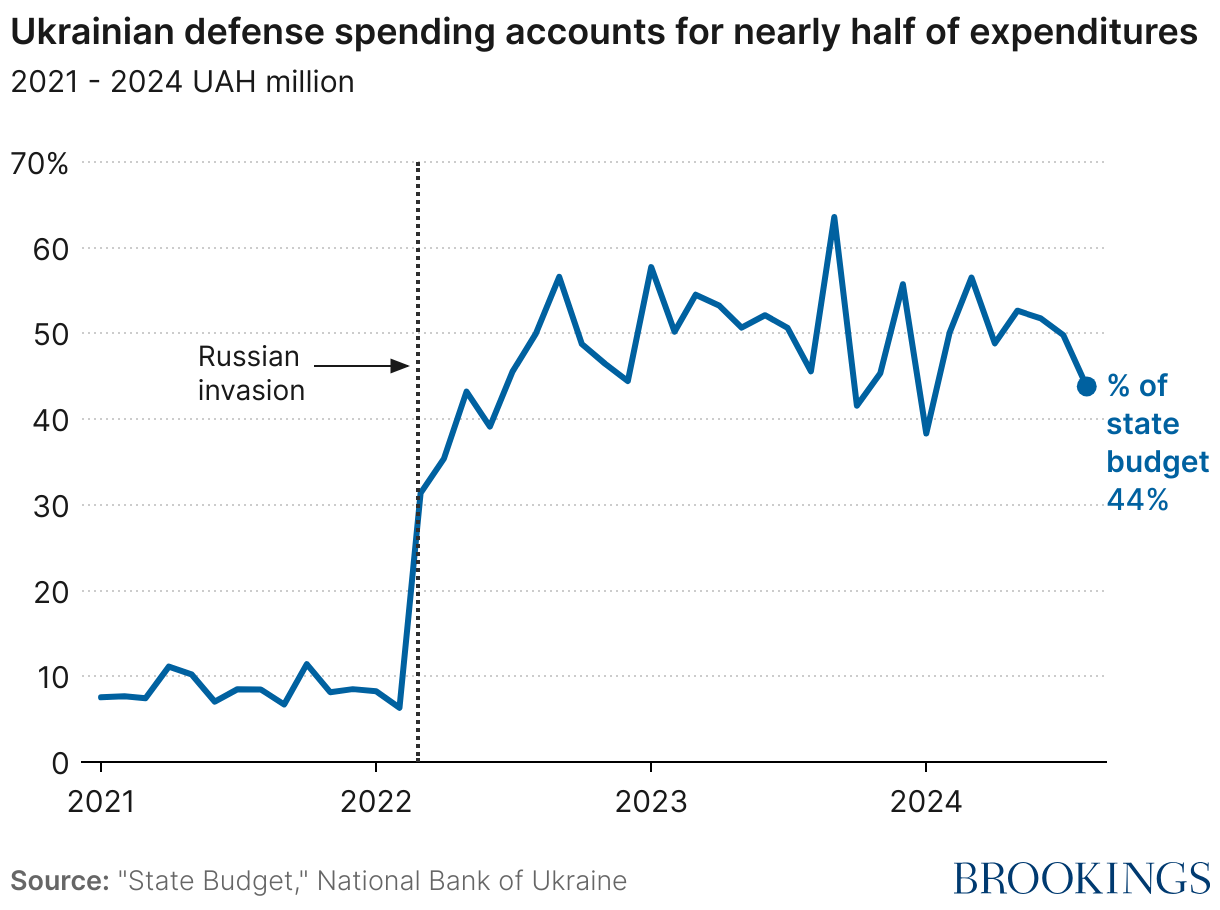

Ukraine also faces a yawning government budget deficit as defense expenditures soar; despite revenues increasing by nearly 50%, they can’t keep up. In 2021, on average, defense spending per month was $390 million, comprising an average of 8.6% of total state expenditures. However, in 2022, on average monthly defense expenditures made up nearly 38% of the budget and that number swelled further to 52% in 2023.2 In the first half of 2024, Ukraine spent 15 times more on defense per month than it was spending before Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Our main focus here is Ukraine’s economy, since it is under the greatest duress. Unfortunately for those wishing to see more pressure on Russia, its economy has plodded along, without any steep hit to GDP. Russia has placed a greater relative emphasis on the military and now benefits from less economic interaction with Western nations, companies, and investors. China has, however, helped Russia make up for the reduced interaction with the Western world. Russia’s aggregate oil and gas exports have continued at substantial levels, albeit with somewhat lower prices than would have been expected without sanctions.

Key political developments

The Russian military has deliberately targeted population centers, civilian infrastructure, and energy networks to terrorize and wear out Ukrainians, blatantly violating the international laws of war and causing millions of Ukrainians to flee their homes. Attacks on the electricity grid have disrupted public services and created difficult conditions as the country prepares for its third full winter since Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Russia’s continued partnership with China as well as its deepening alignment with Iran and North Korea have also aided the Kremlin. NATO has deemed Beijing a “decisive enabler” of Russia for providing critical inputs and technologies for weapons manufacturing and keeping its economy running through trade. Iran has stepped up its contributions of munitions, artillery shells, and unmanned drones with deliveries of close-range ballistic missiles that have devastated Ukrainian cities in near-daily aerial bombardments. Meanwhile, North Korea has sent missiles, ammunition, and artillery shells to expend on the battlefield and, according to recent reports, up to 12,000 North Korean soldiers might soon be sent to Russia to reinforce its manpower. Whether the United States and other international supporters of Ukraine face a new “axis of upheaval” remains unclear—yet in any case, Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea’s increasing alignment is of concern not just for the West, but also for Ukraine’s future.

At the same time, the war has transformed political dynamics at the institutional and civil society levels across the globe in a way that offers hope for Ukraine. Most notably, an international coalition led by G7 countries and the European Union has imposed a series of sanctions to constrain the Russian economy and target individual persons and entities. The sanctions have included several import and export restrictions, particularly on natural resources and technological and industrial goods; a price cap on Russian oil; access to the SWIFT international banking system; seizure of around $300 billion in Russian central bank assets by G7 countries and the EU; and travel restrictions.

In a remarkable feat of public diplomacy, Zelenskyy has spoken to countless foreign audiences to grow and preserve a coalition of support for his country, including national parliaments, business organizations, educational institutions, and cultural gatherings—In addition to his daily video briefings to the Ukrainian people. Ukraine received overwhelming international backing from the U.N. General Assembly in the first year following the full-scale invasion, which voted in six emergency resolutions to condemn Russia’s illegal and unprovoked aggression, demand legal accountability, and urge a comprehensive, just, and lasting peace, among other issues. Nonetheless, Russia has found ways to evade sanctions and remains far from isolated on the global stage.

The European Union formally approved Ukraine’s candidacy status late last year, together with Moldova’s, and moved to open accession talks with the two countries in June 2024. At its 75th anniversary summit in Washington in July, NATO reaffirmed that Ukraine’s future lies in the alliance and that enhanced cooperation with the country is a “bridge” to membership. Together with a broad coalition of international partners, Ukraine continues to defend its territory, sovereignty, and democracy—and with it, the security of the Euro-Atlantic community writ large.

Policy considerations for 2025

This is a backgrounder rather than a policy brief. However, it is only natural to conclude with several key questions that a newly elected American president, European and other foreign leaders, and most of all, Ukrainians themselves, will surely want to ponder in the new year and beyond. We will briefly highlight three broad sets of issues:

Is it realistic for Ukraine to aspire to liberate all of the territory Russia has stolen since 2014? If not, is it more prudent for Ukraine to seek an armistice while maintaining its claims to all of its land, in the hope that someday a political process can return that territory to its rightful sovereign owner even if military operations today might not? Of course, any such negotiations could only work if Russia, too, were willing to change its current demands that it be awarded not only Crimea but all Ukrainian territory within four oblasts: Kherson, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia.

Security architectures. Since 2008, NATO nations have been committed formally and publicly to inviting Ukraine to join the alliance someday. With no date certain and no interim security guarantee, that promise clearly proved impotent in discouraging Russian aggression against Ukraine in subsequent years. Should Ukraine’s membership in NATO now be hastened, perhaps with a special clause to the membership documentation that commits NATO only to defend the territory now controlled by Kyiv? Should it be an irreducible element of any peace deal Kyiv and Moscow might strike in the years ahead, regardless of Russia’s preferences? Are there other security architectures or assurances that might prove equally helpful for Ukraine’s security and also more negotiable with Moscow?

Western assistance for Ukraine. The United States, its European allies, Canada, Japan, and other nations have been remarkably generous to Ukraine since 2022, as we document above. Is it realistic to imagine continuing with such levels of aid indefinitely? For example, might future military assistance focus on air and missile defense and weapons of greatest use for tactically defensive operations (artillery, drones, anti-drone technology, electronic warfare systems, anti-aircraft, and anti-tank missiles), and deemphasize bigger platforms like tanks and fighter jets that Ukraine would likely need in large numbers for any major counteroffensive?

Although the Ukraine war seems largely stuck in place at the moment, there is a good chance that will change—and perhaps even change dramatically—in 2025 or even later this year. The war has been and remains the greatest threat to European security since 1945. Any American president, as well as the new Congress, will need to stay focused on this crucial issue.