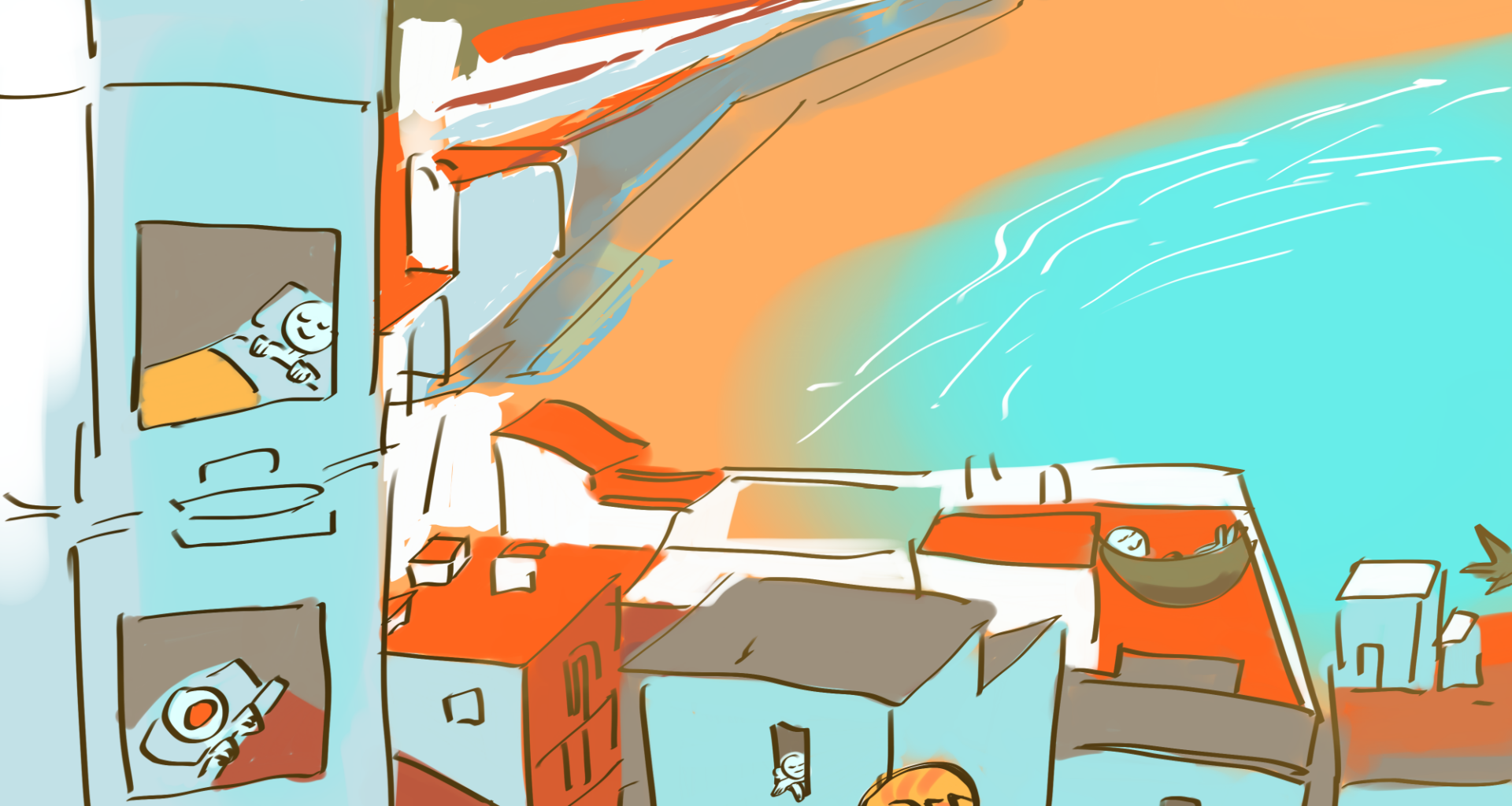

(Shixiao Yu • The Student Life)

(Shixiao Yu • The Student Life)In the United States, everyone naps differently. I’ll often go for a 20 minute power nap if I’m feeling tired and have a lot of work ahead of me. I have some friends who sleep for three hours in the afternoon. Some never nap at all.

In Seville, Spain — where I’m currently studying abroad — napping is a bit more standardized; it takes shape as a cultural tradition known as the siesta.

We often use “siesta” informally to refer to any nap, regardless of when it happens. However, the term originated in Spain, where the siesta is a traditional, longer midday rest that helps people recharge.

Siestas are taken around 3 p.m. and typically last until 5 p.m, during which time shops and restaurants will close and the city will look a little more empty. These naps are especially practical during the hotter summer months, when the afternoon heat can make continuing to work unbearable. By slowing down during these hours, Spaniards can be more productive in the evening when the temperature cools down.

Yet productivity isn’t the goal of a siesta, it’s simply the byproduct. In the United States, we frame napping as a tool to maximize productivity — a quick power nap to recharge and get back to work. The siesta, however, is less about productivity and more about embracing the natural rhythm of the day.

Rest here isn’t something to feel guilty about or optimize for efficiency — it’s an intentional pause, a time to slow down and recharge without the pressure to be immediately productive afterward.

Since coming to Spain, my naps have gotten longer and more frequent. Around four days a week, I’ll nap anywhere between 20 minutes to 1.5 hours, whereas back in Claremont, napping more than 20 minutes was quite rare for me.

Beyond napping, siesta culture has changed my habits and pace of life in other ways, too.

Siestas are associated with Spain as a whole, but they are more customary in some parts than others. Seville is located in Andalucia, where siestas are particularly common due to the region’s hot climate. Andalusian culture is also known to be more laid back than other regions of Spain. Eduardo Pastor, a second-year student at Universidad Pablo de Olavide (UPO) in Seville, sees this culture as unique.

“The culture is very different from the north of Spain,” Pastor said. “Here in Andalucia, we do things at our own rhythm, slowly, without having to take any rush.”

Like many universities in Seville, UPO has classes in session from the early morning to the late night, with classes even running during the typical lunch hour. This means that students who have later schedules often miss out on the luxury of a siesta.

Alba Libraro, another UPO student loves siestas and has taken them regularly since she was a child. Not being able to take siestas due to her schedule was a major adjustment.

“When I stopped doing siestas because of university, I felt it in my body,” Libraro said.

“But when my Google Calendar is full, taking a nap makes me feel guilty. “

She went on to explain how stopping and resuming a siesta routine both pose challenges of their own. Stopping siestas makes Libraro feel mentally fatigued, but getting back into siestas after a prolonged pause is also difficult, as it gets harder to fall asleep in the midday.

For many Sevillanos, giving up siestas is akin to Americans giving up breakfast. Without our most important meal of the day, many of us feel empty in the hours that follow. Likewise, after a hearty rest in the middle of the day, people in Andalucia feel far more productive in the hours before their late dinner.

Here in Seville, I’ve enjoyed allowing myself time to pause and take a rest. When I’m not flooded with commitments, I find myself appreciating the little things more. I feel more present when I’m working out, and more appreciative of my food when it comes time for dinner.

But when my Google Calendar is full, taking a nap makes me feel guilty.

Even in Seville, siesta time can be seen as a hindrance to productivity. UPO student Blanca Alcaide noted that working adults often skip out on these naps.

“In our parents’ generation, [taking siestas] is less common because they don’t have time to do it,” Alcaide said. “But on the weekends and in the summertime, my parents will take a siesta.”

In an increasingly globalized world where Western productivity standards have become more omnipresent, it makes sense that office breaks are under prioritized, even in Seville. And there is something to be said for the rewards of a busy schedule — when done right, it can make us feel fulfilled.

But a healthy level of busyness can very quickly turn into overload. All too often, what we really want to do is take a nap.

Parishi Kanuga CM ’26 is spending her semester abroad in Seville, Spain and would like to shine a light on the study abroad experience for herself and others.

Related