‘Spain in exile has often shown me disproportionate gratitude because the Spanish exiles fought for years and then accepted with dignity the endless pain of exile. I have limited myself to saying that they were right. And for this alone, I have received for years the faithful, loyal Spanish friendship that has helped me to live. This friendship, although I do not deserve it, is the pride of my life. In fact, it is the only reward I can wish for’. This paragraph from ‘What I owe to Spain’, by the Nobel Prize winner Albert Camus, is conspicuously displayed on one of the walls on which hang the graphic testimonies of many of the thousands of people who had to leave their country at the end of the (In)Civil War.

It is estimated that some 13,000 former combatants, politicians, trade union leaders, journalists and activists from the Republican side left the last airfields and ports in planes and boats of various sizes shortly before they were taken over by the Nationalist side.

The exhibition ‘From the Exodus and the Wind. Spanish Exile in the Maghreb’

It was the end of March 1939, when that disbandment headed for the other side of the Mediterranean Sea, in the Maghreb region, the former territories of colonial France, today Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco.

That contingent was later joined by another 4,000 people deported to Algeria from the concentration camps where France had confined them.

All those Spaniards suffered the rigour and harshness of those internment camps, especially those destined for other punishment camps because of their protests, criticisms or insubordination.

The exhibition ‘From the Exodus and the Wind. Spanish Exile in the Maghreb’

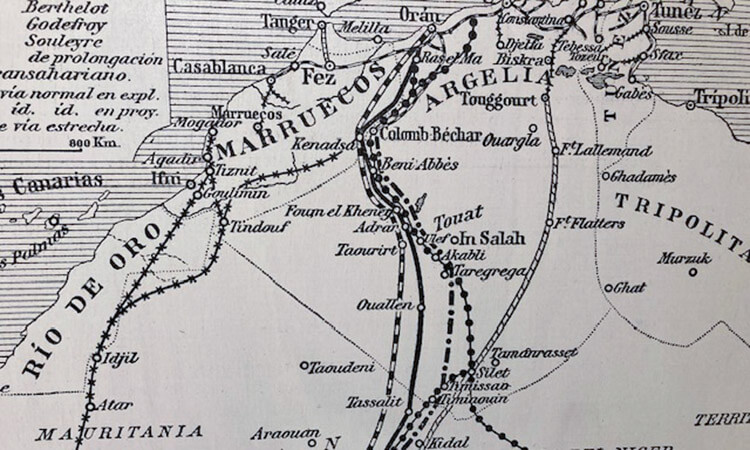

Particularly painful was the fate of the Spaniards who the French authorities assigned to the construction of the Trans-Saharan Railway, the ambitious project to connect the Mediterranean and the Atlantic by train from Algiers to Dakar. Some 2,000 Spanish refugees from Camp Morand were assigned to these jobs in harsh conditions and for miserable wages, which led to strikes, sabotage and protests that the French authorities tried to neutralise with a system of disciplinary transfers to punishment camps, especially the terrible Hadjerat-M’Guil.

The course of the Second World War greatly conditioned the fate of these exiles, who were presented with alternatives. Half of those who arrived in Tunisia returned to Spain after Franco’s regime promised not to retaliate against them.

The exhibition ‘From the Exodus and the Wind. Spanish Exile in the Maghreb’

Hundreds of others were able to travel on to various Latin American countries, requested by family and friends there. Several dozen more, especially airmen, agreed to be taken to the USSR, and many others were offered the alternative of enlisting in the Allied armies to fight on the battlefields of Europe.

Some were not shy of loudly expressing their complaint: ‘The French have treated us like dogs and now they are asking us to go and liberate them’. In the end, those who died in the concentration and labour camps had no choice.

The exhibition ‘From the Exodus and the Wind. Spanish Exile in the Maghreb’

Among those who chose to enlist in the ranks of the French Resistance against the collaborationist Vichy regime, the barely a hundred and a half expatriates who made up La Nueve, the company that spearheaded the liberation of Paris, where they entered on board their armoured vehicles with the names of the battles they had lost in the Civil War tattooed on them, stand out.

On display in the exhibition is a photograph in which all the members of the company pose in full in the United Kingdom before landing in Normandy in 1944 with the aim of liberating the French capital from Nazi power. Next to it, another photo shows the car that opens the triumphal parade on the Champs Elysées, on board of which Amado Granell sits next to General De Gaulle.

The exhibition ‘From the Exodus and the Wind. Spanish Exile in the Maghreb’

It took José Miguel Santacreu, scientific curator, and Juan Valbuena, visual curator, two years to put together this exhibition, which offers a historical and emotional journey in two spaces, marked by a chronology and very defined feelings, which oscillate between fear, indignation, hope and resignation.

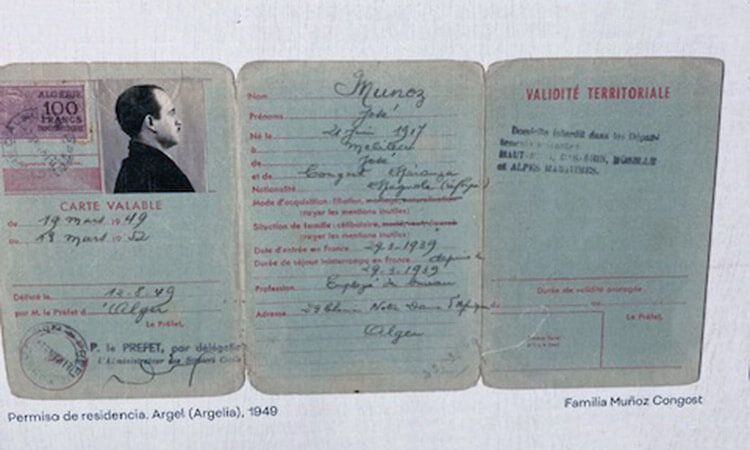

At the end of the independence processes in the region, in 1962, some 2,000 Spaniards remained in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, many of whom had integrated with the local population, adapting to the ways and customs of their new life.

The exhibition ‘From the Exodus and the Wind. Spanish Exile in the Maghreb’

All of them always carried in their hearts and memories the Spain where they were born. But many of them would never see it again because death, for one reason or another, took away forever their secret longing to return.