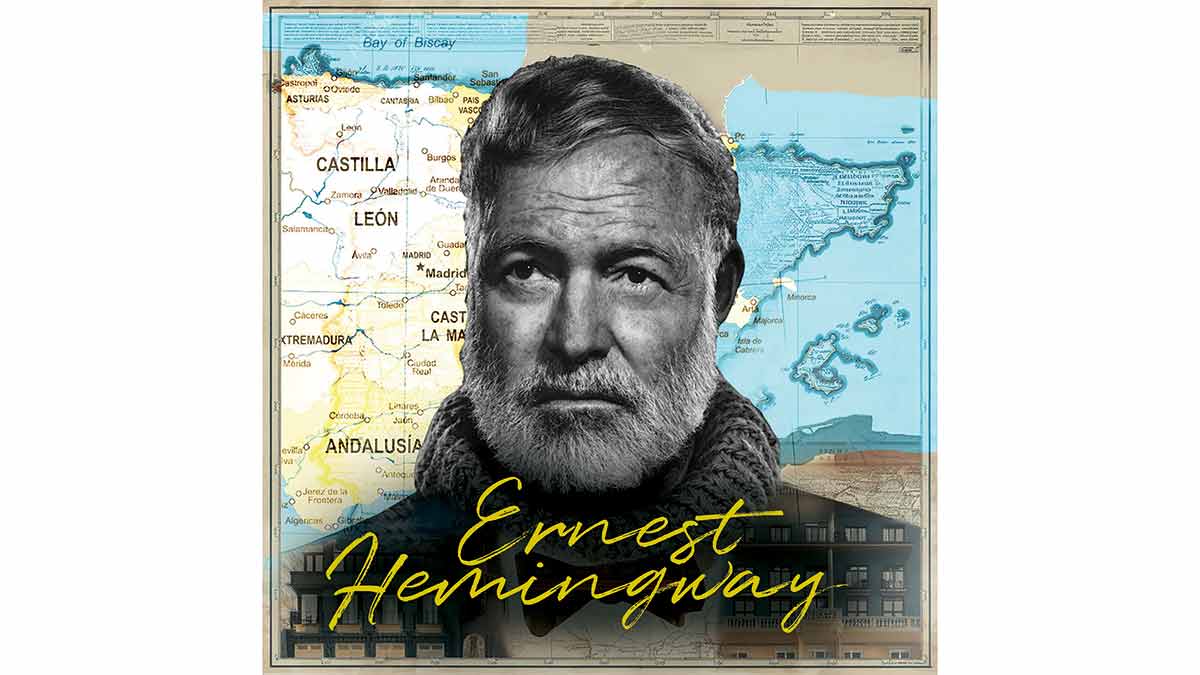

There are no other countries like Spain,” says Robert Jordan in Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bells Toll. The same belief propelled Hemingway’s four-decade-long love affair with the land that inspired his best work, including several novels and some of his finest short fiction. In return, he left his own indelible stamp on Spain’s global perception, creating unforgettable images of a country steeped in passion and romance, and of a people who lived and loved hard, and often died without compromise.

Apart from writing up the bull fights of Pamplona and trout fishing in the Pyrenees, he also left a boozy trail in the squares and winding lanes of old Madrid. He immortalised the restaurant Botin, by calling it “one of the best restaurants in the world” in his first novel The Sun Also Rises. Reservations are difficult to get in this old-world place known best for its roast suckling pig and milk-fed lamb but the crowds keep on coming; in fact a neighbouring restaurant vented its frustration by advertising, “Hemingway did not eat here”.

The charming Cerveceria Alemana with its wood-panelled walls, blackened paintings and black and white bull-fighting photographs speaks of a time gone by; Hemingway’s usual table looks onto the Plaza de Santa Ana—a square where old men play chess with giant pieces and students gather around a statue of the Spanish writer Federico Garcia Lorca. There are other haunts, too—mostly bars and cafes—but to follow Papa’s trail to the last cocktail is to put one’s own liver at serious risk.

The Sun Also Rises may never have been the literary success it became but for detailed editorial suggestions from F. Scott Fitzgerald, already a well-known author and Hemingway’s friend, including the deletion of much of the opening chapter that smacked of “condescending casualness”. Hemingway, being Hemingway, followed the advice but later denied that Fitzgerald had made any contribution.

Fitzgerald, too, was not unaffected by Spain. Nick Carraway, the narrator of his best novel The Great Gatsby, is left desolate and disillusioned after Gatsby’s death. He is haunted by the deep distortion he sees in the east (of the United States). In a nightmarish vision of West Egg, the scene of much drama in the book, he compares it to “a night scene by El Greco: a hundred houses, at once conventional and grotesque, crouching under a sullen, overhanging sky and a lustreless moon”.

El Greco lived and painted his best canvases in Toledo, which rises from a rocky outcrop an hour out of Madrid. Skirted respectfully by the Tagus River, it is unreal and out of time. Its monochromatic and moody beauty—shades of stony beige—whispers like old wealth; its quiet dignity envelops two thousand years of history—from Rome to the Visigoths to the Umayyads and the Christians—in its ancient stones and streets and in its churches, buried mosques and synagogues.

El Greco was all tortured conflict and hypnotic intensity—the elongated figures, the complex entanglements, the pain and the anguish. One of his most remarkable canvases is the famous landscape View of Toledo in which, under a sombre and imminently violent sky, Toledo lies in surreal disarray, and even the massive cathedral has been moved. Nick Carraway’s sense of distortion that goes beyond his “eyes’ power of correction” is perfectly understandable: one only has to stare long enough at Toledo rising into what Hemingway described as, “the high cloudless Spanish sky that makes the Italian sky seem sentimental”.

The writer is former ambassador to the US.