If the United States had an aristocracy, the Kennedy family would be at the forefront. Of the nine children of Joseph and Rose Kennedy, three are inscribed in the public’s memory: former US president John, presidential candidate Robert and senator Ted. The assassination of the first two, both Democrats, rocked America and the world in the 1960s, while the third will always be remembered for a car crash that killed his secretary. The other six never acquired a reputation outside the US and this is why anyone who knows Tom Shiver but doesn’t know he’s the son of Eunice Kennedy Shiver may not understand why he looks so familiar.

From the shape of his face, his nose, the side parting and smile, Tim Shiver brings to mind his mother’s brother John. And even though he comes from America’s political aristocracy, he is disarmingly modest, approachable and affable. He sits beside me at the MET Hotel in Thessaloniki, with one hand on the back of the couch, wearing a plaid blazer and sneakers.

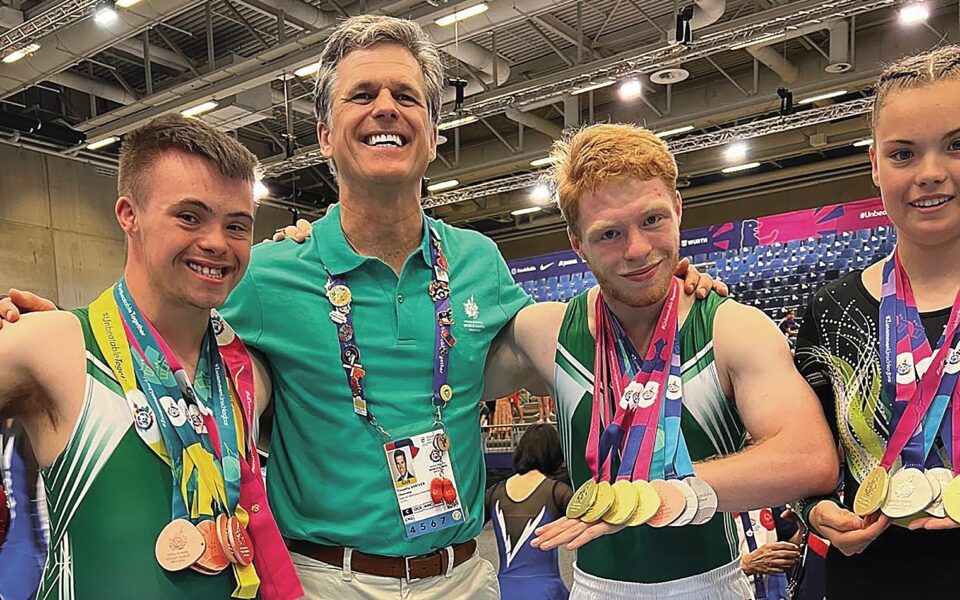

He’s in the northern port city because, as chairman of the Special Olympics, the world’s biggest athletic event for youngsters and adults with intellectual disabilities, he is this year’s recipient of the prestigious European Empress Theophano Prize. This is not his first time in this country. “I’ve been dozens of times. I love Greece,” he tells Kathimerini. But this visit is quite special.

“It’s a humbling honor. I have to pinch myself,” he says with a beaming smile. “This is a prize that celebrates a thousand years of European history, the biggest ideals of Greece and Europe. And it’s now being given to the humblest and most overlooked people that have ever lived on this continent,” he adds, referring to the athletes of the Special Olympics, which takes place all over the world, including Greece, which hosted the games in 2011.

A lot has changed since Shiver’s mother established the institution in 1968. For the first 30 years, no country except the US was interested in hosting the Special Olympics. The athletes were practically unknown, even in the US, with attendance often being in the single digits, even in stadiums for 50,000 people. No one really cared about people with intellectual disabilities.

Things are much better today. “Healthcare has improved the lives of people with intellectual disabilities. We had the first generation of people growing old. Historically, people with intellectual disabilities died quite young,” says Shiver. There are also schools and jobs for them, he adds, citing companies like Coca-Cola, Toyota and United Airlines that are hiring people with intellectual disabilities. The Special Olympics are also broadcast by mainstream sports channels like ESPN and Eurosport. “Their Olympic achievements are being recognized.”

However, adds Shiver, there is still a lot of room for improvement. “We see exclusion in healthcare systems, in schools, in communities, from the workforce. We see parents who are still laboring financially to provide for their children, to protect their children from humiliation and scorn by society,” he says. “It is still common to mock people as being stupid or mentally retarded, deficient – we still see this language, it’s still common.”

That said, “there’s an increased understanding that human diversity is a gift,” he adds.

This understanding lies at the heart of the Special Olympics. “The measure of success for Special Olympics athletes is not your outcome. It’s your effort. That’s a huge lesson for me,” Shiver tells Kathimerini.

Another stems from the athlete’s resilience and persistence, and their trust and openness towards others. “I mean, our athletes get treated so badly, and yet they almost very rarely don’t take a chance another time,” he notes. Above all else, these athletes teach us that everyone deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. “That’s the basic premise of this movement.”

Shiver may not have gone into politics as other members of his family did, but he tries to make the world a better place, not just through the Special Olympics but also through the Unite initiative, whose aim is to “change the culture.”

To this end, they created a dignity index which scores how people treat those they disagree with. “A one is you don’t deserve to live – and we see this in political discourse,” he notes.

The way we disagree can lead to violence, isolation and despair. “If I call you disgusting because you like a left-wing party and I like a right-wing party, that’s cancellation. It’s a destruction of the very nature of relationships when we dehumanize each other. So Unite is trying to create a scale that invites people to learn how to see themselves and also learn how they can disagree with dignity,” explains Shiver.

The initiative has also created a program that teaches people how to treat others with dignity and it has taken it to universities and big corporations like the Bank of America. “We have trained around 6,000 employees and several United States governors,” he notes.

Shiver believes that people are “exhausted by contempt” and “starving for change.” They’re also anxious, and especially young people. He also believes that religion can serve as an answer to this anxiety. “Religion at its best is the cultivation of your hunger for ultimate meaning and value. That’s what religion starts with. It’s a search engine.”

Shiver is also concerned about the United States, which he says is in the grips of a “crisis of contempt.”

“And contempt is threatening to everyone. Political differences are healthy for everyone, contempt is not,” he says. “So I worry about the election, dividing the country further and making more people treat more of their fellow Americans with contempt. I worry about the extent to which either candidate will produce a reduction in contempt and hatred and dehumanization.”

Despite the concerns, Shiver is fundamentally optimistic and believes things will get better. “If we can get politicians to be less contemptuous and less dehumanizing to one another, and if we can get the algorithm to stop rewarding fear and dehumanization, I think we have a chance,” he says.

Indeed, Shiver is the author of “Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most” and what he believes is that “love’s what binds us together” and what matters most. “The capacity to feel it, to give it, to trust that it’s there when it doesn’t feel like it is.”

I ask whether being a member of the Kennedy family has been a burden and he sits back a bit, puts his hands together. “Well, if it was, I got through it. You know, everything’s a little bit of a burden. Everything’s a little bit of a gift. I mean, I have had a lot of people being unnecessarily and unjustifiably kind and helpful to me in my life. And I’ve had my fair share of painful and difficult moments. Is that because of my family? Some of it has nothing to do with me. And you know, on measure, others paid a very high price for some of what my family has been given. And that’s heartbreaking.

“So I see it, in general, as a great gift I was given to have access to and potential to participate in things that matter,” he says.

His immediate family, his mother and his father, who was the first director of the Peace Corps, taught him that duty and service are not a burden but a joy. “That’s what service does: It allows people to bridge a gap, to heal a divide,” he says. “And when you heal a divide, both sides win.”