In June 2016, the manifestos of In Common We Can (ECP), Commitment (CMP), and In Tide (EM) featured well-developed, standalone sections on both climate change and energy transition. Citizens (Cs), while having a shorter section, also included a well-articulated part on climate change with a subsection on sustainable energy. Together We Can (UP), Canarian Coalition— Nationalist Canary Party (CC-PNC), the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), and the People’s Party (PP) also dedicated entire segments to energy issues. While UP included clearer measures on climate change within a broader section devoted to environmentally related topics, the PSOE, Cs, and the PP addressed these issues more sporadically, essentially within their energy sections. The ERC’s manifesto showed a similar trend, approaching both topics in a more general context. The Democratic Convergence of Catalonia (CDC) and the Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ-PNV) addressed these topics within a general environmental section, whereas Unite the Basque Country (EHB) did not include any significant development of them.

In the November 2019 elections, More Country—Equo (MP-E) distinguished itself with a thorough approach to both climate change and the energy transition, addressing each explicitly in the first and second sections of its manifesto, and more generally in the final two sections. Similarly, both CMP and ECP allocated an independent section to each topic. EAJ-PNV, Canarian Coalition—New Canaries (CC-NC) and Together for Catalonia (JxC) also included sections exclusively focused on clean energy. EAJ-PNV and CC-NC used these sections to also cover climate change, while JxC developed this topic more thoroughly in a separate environmental section. In the same vein, UP, ERC, and BNG wrote in length on both issues within broader sections on environmental protection. The PSOE, Cs, and the PP did so to a far lesser degree of refinement. Manifestos from Candidacy of Popular Unity (CUP), EHB, the Regionalist Party of Cantabria (PRC), and Teruel Exists (TE) generally addressed related topics rather than focusing on climate and energy directly, which nonetheless stand out proportionally due to the brevity of these documents. Sum Navarre (NA+) made only scant mentions of these issues throughout their texts, and VOX did not address them at all.

By July 2023, Unite had included two distinct sections on climate change and the energy transition. BNG, the ERC, the PSOE, and the PP each dedicated a section to the second topic and addressed the first one within a broader environmental context. EAJ-PNV, JxC, and EHB also had similar sections on energy, with climate change mentioned transversally across their texts. Without specific sections on any of them, we find mentions of both topics among the measures proposed by the Canarian Coalition (CC), and less often on renewable energy in those of Navarrese People’s Union (UPN) and VOX. Based on the structural evolution of the manifestos studied, there is no discernible pattern in the overall emphasis they place on the analyzed issues. For instance, although political parties are more frequently addressing climate change within broader environmental sections, these areas have gradually become more extensive and comprehensive over time. Therefore, to more accurately assess the significance of climate change in the Spanish elections of June 2016, November 2019, and July 2023, I conducted a quantitative study based on the two variables designed specifically for this purpose.

Table 1 (and Supplementary Figs. 1–3) presents the percentage of content related to each category of the ‘climate code’ variable by political party. The results indicate a significant focus on ‘pro-climate’ content in the manifestos of the political parties studied, with higher figures observed in the 2019 elections. In 2016, CMP, UP, EM, and Cs stood out for assigning greater importance to this category in their manifestos. In 2019, the MP-E coalition dominated, thanks largely to the participation of EQUO, whose environmentalist stance is notable in a country where green policies have traditionally been non-existent at the central level (McFall 2012). Behind this alliance, CMP, EHB, TE, UP, and EAJ-PNV also stand out. Turning to the 2023 elections, parties such as Unite, which filled the ideological space left by UP in previous elections, EAJ-PNV, BNG, and the PSOE were the most vocal on ‘pro-climate’ issues. It is noteworthy that VOX and the PP occupy prominent positions in terms of ‘anti-climate’ content in their manifestos, although they are sometimes surpassed by the PRC and TE in 2019, or UPN in 2023.

When it comes to the study of specific ‘pro-climate’ policy subcategories, further variations exist (Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. 4–6). The results of the second, more detailed assessment of ‘pro-climate’ policy importance indicate that the political parties in question generally place greater emphasis on ‘pro-environment’ content in their manifestos, which is logical given that it is the most comprehensive category within the variable it belongs to, followed by ‘pro-lower carbon transport’, ‘pro-renewable energy’, and ‘pro-carbon sinks’. In particular, CMP, UP, and Cs placed notable emphasis on the three aforementioned categories in 2016. Turning to 2019, UP shared this focus with MP-E, which also paid significant attention to these categories, whereas EHB, for instance, almost exclusively focused on ‘waste’ and ‘agriculture and food’. In addition, it is worth noting the figures of other parties, such as CMP, which place special emphasis on ‘pro-energy efficiency’. In 2023, the shift in ideological competition space from UP to Unite is reflected in Unites’ greater emphasis on ‘pro-climate’ categories similar to those previously advocated by UP. It is also worth highlighting the significant emphasis placed on ‘renewable energies’ by EAJ-PNV and BNG.

The most notable ‘anti-climate’ categories in 2019 include ‘pro-growth’, ‘pro-roads’, ‘pro-aviation and maritime transport’, and, to a lesser extent, ‘anti-taxes’, with ‘pro-intensive agriculture’ and ‘pro-fossil fuels’ gaining momentum from 2023 onwards. While in 2016, it was the PP that dominated this aspect due to its focus on ‘pro-growth’ issues, it shared its leadership in this category in 2019 with VOX, JxC, and EAJ-PNV. Interestingly, driven by the specific needs of the regions they represent, CC-NC and TE have begun to excel in their use of ‘pro-aviation and maritime transport’ and ‘pro-roads’, respectively. A similar trend persists in subsequent elections, with the most notable development being the increasing use of ‘pro-fossil fuels’ content by PP and VOX.

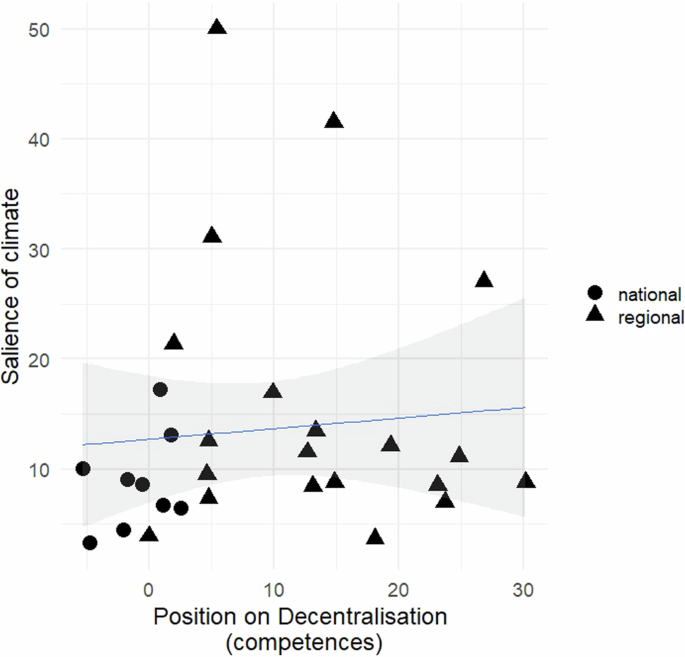

The percentages shown in Tables 1 and 2 provide initial support for hypotheses 1 and 2. While these figures highlight the increased emphasis on climate change among left-wing parties, we find notable exceptions, such as the center-right parties CDC/JxC in 2016 and 2019, as well as EAJ-PNV in 2019 and 2023. This indicates that although political ideology likely influences climate policy preferences, it is true that NSWPs—compared to most SWPs, including some left-leaning ones like the PSOE in 2016 and 2019—pay greater attention to climate issues. To confirm or reject the first hypothesis it is necessary to examine the link between decentralization and climate policy preferences (Figs. 1 and 2). The data indicate that parties exhibiting a stronger pro-decentralization stance along the center-periphery axis tend to place greater importance on climate content in their national election manifestos. Similarly, the results in both figures reveal that the NSWPs, which are the actors most in favor of decentralization, consistently exhibit the highest values regarding the importance of climate issues.

Source: The scores on the salience of climate are calculated from the data shown in Table 1. The scores on decentralization are based on Supplementary Table 1. Legend: The variable ‘salience of climate’ accounts for the total percentage of quasi-sentences that each party manifesto dedicates to ‘pro-‘ and ‘anti-‘ climate content. ‘Pro-climate’ quasi-sentences refer to those that promote policies aimed at reducing GHG emissions or increasing GHG sinks, while ‘anti-climate’ quasi-sentences refer to those that advocate for policies leading to increased GHG emissions or reduced GHG sinks. The variable ‘position on decentralization’ reflects the difference between the percentage of quasi-sentences that support decentralization and those that oppose it in each party’s manifesto. Parties represented by triangles belong to the Non-Statewide Party (NSWP) category, while parties represented by circles belong to the Statewide Party (SWP) category.

Source: The scores on the salience of climate are calculated from the data shown in Table 1. The scores on decentralization are based on the Manifesto Data Collection (MRG/CMP/MARPOR)60. Legend: The variable ‘salience of climate’ measures the percentage of quasi-sentences that each party manifesto dedicates to ‘pro-‘ and ‘anti-‘ climate content. ‘Pro-climate’ quasi-sentences refer to those that promote policies aimed at reducing GHG emissions or increasing GHG sinks, while ‘anti-climate’ quasi-sentences refer to those that advocate for policies leading to increased GHG emissions or reduced GHG sinks. The variable ‘position on decentralization’ reflects the difference between the ‘Decentralization’ and ‘Centralization’ variables from the MRG/CMP/MARPOR60. Parties represented by triangles belong to the Non-Statewide party (NSWP) category, while parties represented by circles belong to the Statewide party (SWP) category.

This finding is reflected in the manifestos of notable pro-decentralization parties, which express the regions’ desire to manage the resources and competences related to climate change:

‘Transfer the proceeds from the auction of emission rights to the Government of Catalonia for them to be allocated to the fight against climate change’46

‘Demand for the resources allocated to research and the implementation of policies for mitigating and adapting to climate change to be distributed among the territories of the ACs’47

‘In terms of jurisdiction, we advocate for the transfer of all environmental competencies to Galicia’48

‘We will provide municipalities with the necessary resources for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions’49

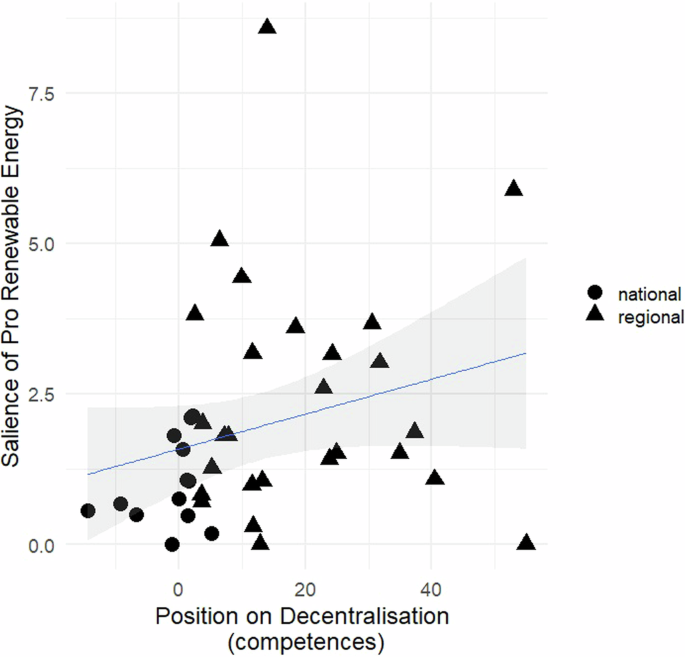

To test the second hypothesis, I analyze the association between the position on decentralization and the salience of ‘pro-renewable energy’ (Figs. 3 and 4). Especially noteworthy is the first figure, which is more comprehensive as it includes data from the 2023 elections; in particular, NSWPs like EAJ-PNV, BNG, and UPN dominated the last-mentioned category. This (more clearly) evinces the existence of a positive relationship between the two variables: Political parties that adopt a more pro-decentralization stance tend to place greater emphasis on pro-renewable energy in their national election manifestos. Again, the results in both figures reveal that the NSWPs generally exhibit the highest values concerning the importance of the RET.

Source: The scores on the salience of renewable energy are calculated from data shown in Table 2. The scores on decentralization are based on Supplementary Table 1. Legend: The variable ‘salience of pro-renewable energy’ measures the percentage of quasi-sentences that each party manifesto dedicates to advocating for the shift in the production, distribution, and consumption of electricity from conventional, fossil fuel-based sources to sustainable and renewable energy sources. The variable ‘position on decentralization’ reflects the difference between the percentage of quasi-sentences that support decentralization and those that oppose it in each party’s manifesto. Parties represented by triangles belong to the Non-Statewide party (NSWP) category, while parties represented by circles belong to the Statewide party (SWP) category.

Source: The scores on the salience of renewable energy are calculated from data shown in Table 2. The scores on decentralization are based on MRG/CMP/MARPOR60. Legend: The variable ‘salience of pro-renewable energy’ measures the percentage of quasi-sentences that each party manifesto dedicates to advocating for the shift in the production, distribution, and consumption of electricity from conventional, fossil fuel-based sources to sustainable and renewable energy sources. The variable ‘position on decentralization’ reflects the difference between the ‘Decentralization’ and ‘Centralization’ variables from the MRG/CMP/MARPOR60. Parties represented by triangles belong to the Non-Statewide party (NSWP) category, while parties represented by circles belong to the Statewide party (SWP) category.

This aligns with the demands expressed through various quasi-sentences identified in the manifestos. In these, the NSWPs demonstrate awareness of their regions’ potential for renewable energy generation and the opportunities it provides them:

‘The potential for renewable energy generation, thanks to the abundant resources (wind and sun), along with the high investor interest, should be leveraged to develop renewable installations that meet current electrical needs, future needs driven by the electrification of other types of consumption, and for the production of green hydrogen’50

‘The set of energy policies and climate change adaptation measures harbor significant employment opportunities and the capacity to stimulate the economy’51

Similarly, they often emphasize the detrimental impact of the state’s recentralizing and extractive role regarding this issue:

‘The actions of the central government regarding the energy sector in recent years have been characterized by a clear process of recentralizing some of the competencies granted to the ACs’52

‘The BNG will advocate in all areas, and particularly in the Cortes, for overcoming a dependent and extractive model that has turned Galicia into a provider of raw materials and energy, with extremely high social and environmental costs’48

‘The reform of the electricity sector driven by the State has negatively impacted electricity generation installations based on cogeneration, renewable energies, and waste. In Catalonia, 3866 installations have seen their premiums reduced from 732 million euros to 543 million euros, resulting in a loss of incentives amounting to 189 million euros and a reduction in remuneration of more than 25%’ 47

Accordingly, the NSWPs consistently advocate for decentralized renewable generation:

‘It is necessary to defend our right to choose our own energy model, to contribute to the fight against the climate crisis, and to do so in a way whereby the productive role benefits the social and economic interests of Galicia while safeguarding the preservation of biodiversity’48

‘In particular, the State will be urged to implement specific measures to accelerate the energy transition in the Canary Islands (considering that in isolated and insular territories such as the Canary Islands, it is more challenging to undertake the necessary changes for the new energy paradigm)’53

‘The energy transition towards a system where demand is predominantly met by renewable energies implies a progressive electrification of consumption and increasingly decentralized generation—one of smaller size and that is closer to consumption points’50

‘The energy transition towards a 100% renewable model must be based on the decentralized production and management of energy, which means that the role of local administrations—alongside citizens and the cooperative movement—is crucial in a self-production-based model.’49

‘We must shift towards a decarbonized model without nuclear power plants – a decentralized one in which renewable energy is self-produced locally—to achieve the goal of zero GHG emissions by 2050’54

The evidence gathered from the data confirms the two hypotheses of this study. Given the consistent positive correlations observed, it is reasonable to suggest that political parties with stronger pro-decentralization inclinations tend to prioritize climate change and the RET in Spanish national elections. The positive relationship between devolution and the advancement of climate policy and the RET supports a decentralized approach to both issues as decentralization raises the efficiency and legitimacy of climate management.

To this end, lower levels of government empowered within decentralized systems are best equipped to tailor their actions to local conditions, thereby leveraging local knowledge, skills, and resources to promote effective climate policies5. Such an approach also enhances responsiveness and efficiency in addressing region-specific needs while balancing land use and environmental considerations of the RET14,18. Moreover, decentralization plays a crucial legitimizing role by granting autonomy to regional entities in developing and implementing climate policies5,9. It also promotes models of ‘energy democracy’, where active citizens engage in renewable energy production and consumption21,22. Lastly, subnational governments can play a complementary or compensatory role in national climate action3,12,13. Specifically, they can contribute to realizing the RET by decreasing their energy dependence on the central government and developing their own renewable energy strategies and policies when they possess the necessary jurisdictional capacity15.

On a different note, NSWPs may have additional, territorial motivations that partly explain the presented findings. While it would exceed this study’s scope to compare the specific roles of these parties versus Statewide parties (SWP)—some of which, in the Spanish context, sometimes adopt pronounced pro-decentralization positions due to the significance of this divide—NSWPs assert leadership in both areas. As highlighted in the existing literature on Green Nationalism in regional elections45, their leadership on climate and renewable energy issues at the central level would be motivated by a desire to challenge the institutional status quo of the State and enhance the autonomy of the regions they represent37,38,39. Indeed, as shown by the quasi-sentences quoted above, NSWPs often invoke climate change to pursue greater economic and/or political autonomy at the substate level3.

In accordance with the above, the evidence in Figs. 3 and 4 shows that pro-decentralization parties are interested in acquiring higher autonomy with respect to energy-related issues. This interest would stem from the potential control that regions could wield over the growing network of renewable energy installations during the RET. In turn, the NSWPs could increase their political clout with regard to energy policy and, at the same time, decrease the dominant position of the state as the leading energy supplier.

This paper contributes to the theoretical development of Climate Federalism, as empirical evidence from the analysis illustrates that the underlying pro-decentralization orientations of political parties are likely to put greater emphasis on climate change and the RET, for which reason they often assume climate leadership in multilevel democracies. The findings also highlight the strategic role of subnational politics in shaping national climate agendas, reinforcing the notion of Green Nationalism as a critical framework for understanding climate leadership not only at the regional level but also at the national one. This paper thus fills the gap between decentralization and climate policy preferences by informing academic debates on how the support of climate policy can be enhanced under multilevel governance systems through interparty competition by subnational actors seeking regional self-government.